Acans (Micromussa lordhowensis)

The pillowy little polyps of the Acan or Lords Coral are one of the most common and colorful sights in fish stores, but, thanks to a recent change in nomenclature, this coral is now woefully misnamed.

The common name Acan derives from the genus Acanthastrea, which is a group that has seen some pretty drastic changes of late. This first became apparent in a molecular study published in early 2014 which highlighted the many inadequacies of how we had been classifying the Indo-Pacific brain corals.

The next year saw the infamous Acanthastrea maxima (frequently misidentified in the aquarium trade, as it has never been imported) into a new genus, Sclerophyllia. At the very end of 2015, a major revision of this group appeared which moved A. ishigakiensis into Lobophyllia and A. faviaformis among the corals formerly known as Favia (now Dipsatrea). Remarkably, these belong to completely different families now. And lets not forget the peculiar A. regularis, which found a new home among Micromussa. But none of these species were of much concern to the aquarium trade.

But in 2016, some major changes happened to species of more importance. The large, multi-polyped A. hillae was synonymized into A. bowerbanki, and this coral was moved alongside the scoly into the new genus Homophyllia. And the topic at hand is that the ubiquitous Acanthastrea lordhowensis found itself relocated into Micromussa, where it now resides alongside the coral that it was always most easily confused with, its small-polyped cousin M. amakusensis. And so, in 2019, Acanthastrea is a shell of its former self, with only a couple species that actually find their way into aquariums.

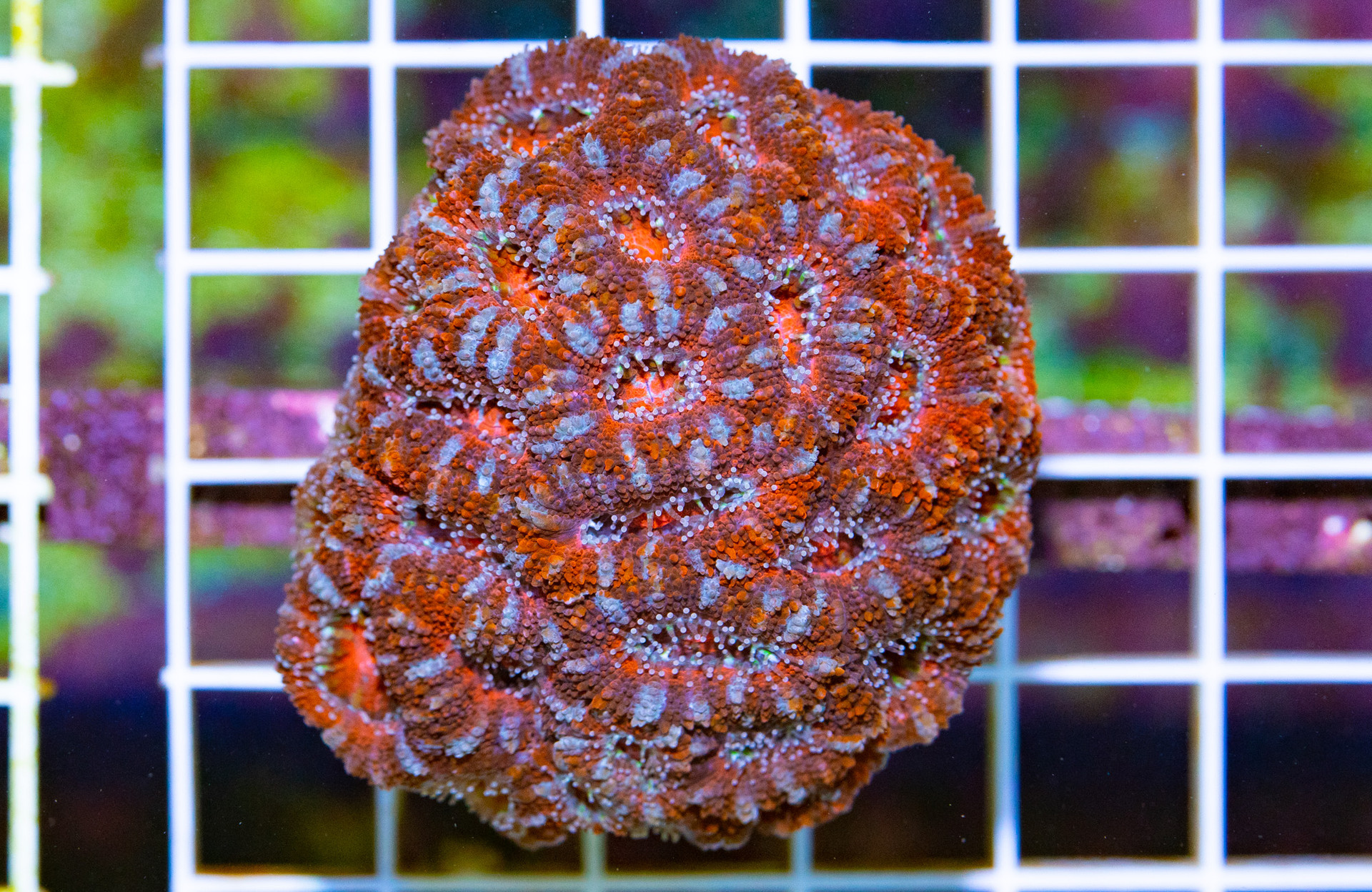

But putting aside all this taxonomic esoterica, M. lordhowensis is well-deserving of its popularity among aquarists. It demands little in terms of lighting or water flow, and, if fed regularly on meaty foods or pellets, it will bud off new polyps with surprising quickness. Colonies never grow especially large, but the fluffiness of the tissue makes even a small number of polyps seem larger than one might expect. They are highly variable in color and patterning, from solid red specimens to teal and pink striped polyps. And they pose little danger to nearby corals, nor are they easily damaged. A perfect coral?