Scoly (Homophyllia australis)

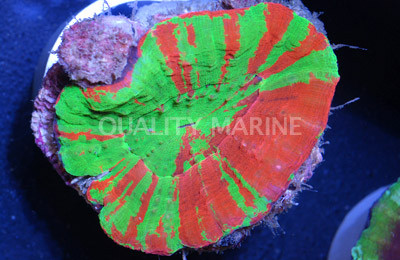

For the past decade or so, one of the most dominant corals in the aquarium trade has been a colorful, circular species known far and wide as the scoly. Specimens come in a bewildering array of colors, from those that are primarily red or green, to those especially resplendent polyps that are given the name Master Scoly and feature a veritable pinwheel of tie-dyed colors.

The common name of scoly derives from the longtime placement of this species in the genus Scolymia, but morphological and molecular work done on stony corals in the past decade revealed that the scoly familiar to aquarists was in fact a very distant relative of the true Scolymia, whose three species are now known to exist only in the West Atlantic.

The differences between these corals are not especially apparent at first glance, as all of these species are typically solitary and round (though multi-polyped specimens do show up on occasion). The diagnostic traits are revealed in the fine structure of the skeleton, particularly the shape of the spines on the septa (which have a nasty tendency to poke through the tissue when these corals are handled roughly). In the true Scolymia, the spines are finer and more cylindrical, while those in the Pacific species are blunted and hillocked. Along the sides of each septa are a number of fine bumps, termed granulations, which are much less numerous in Scolymia, and the granulations found on the septal teeth are arranged differently as well.

In addition to these seemingly minor differences, genetic data points to Scolymia in the Atlantic belonging to a very different branch of the stony coral tree, closely aligned with other LPS type corals in the Atlantic. This group is now known as the Mussidae. On the other hand, the Pacific scoly falls among the brain corals in the Merulinidae, a family restricted to the Indo-Pacific. So since it wasnt actually a Scolymia, the scoly desperately needed a new name, which is how it got rebranded as Homophyllia australis.

In captivity, the scoly is a quintessential LPS coral as far as its care requirements go. It comes from relatively turbid areas in the wild, where it grows in low abundance on solid substrates. In captivity, youll want to give it low to medium light and minimal water flow. Too much flow, and the tissue will smash against the skeletal septa and tear.

Feeding should be considered a requirement to keeping H. australis. Meaty foods liked chopped fish or shrimp can be placed near the mouth, which the polyp will quickly engulf into its greedy scleractinian mouth. Overfeeding is a definite possibility, which can lead to food decomposing inside the polyp before digestion can complete, potentially sickening the entire organism. Once or twice weekly feedings is plenty. The tentacles are relatively short and pose little risk to neighboring corals unless in direct contact.