The Mechanics of Mechanical Filtration

We're back today working on part two of our filtration series. Last week we covered the basics of chemical filtration, and today we're looking into mechanical filtration. This means the physical removal of particulates from your aquarium water. Mechanical filtration only removes particulate waste, though often these particulates are composed of fish waste or uneaten food, and so removing them also has a biological impact. More on this in next week's article!

All mechanical filters are rated by something called “Micron Size.” This relates to the size of particle that can be caught in the filter. Commonly seen sizes are one, five, ten, twenty microns, and then bigger jumps happen, 50-, 100- and 200-micron filter media is not uncommon, though the high end of this is of questionable benefit. Micron measurement is utilized by other industries and is a metric standard. The term micron is actually an abbreviation for a micrometer, which is 1/1000 of a millimeter. It isn't uncommon in the beverage industry to utilize a .45-micron filter size, which is small enough to remove bacteria! On the other end of the spectrum, 50 microns is about the diameter of a human hair. It will remove sand, dirt and other large particles. Whole house water filters are usually in the one-to-five-micron sizes.

Over the years of captive aquatics, many different mechanical filters have been utilized, each with benefits and drawbacks. One of the primary drawbacks of all mechanical filtration is that it needs to be very regularly cleaned or replaced. There was once a popular argument that aquarists should use larger micron filters because they needed less frequent replacing. Indeed, they did not get clogged as quickly, but they left a lot of particulate material suspended in the water, which then had time to dissolve and complicate biological filtration, while doing little to improve the clarity of the water. Obviously, on the other end of this spectrum, we don't need or want to remove bacteria from our tanks, and so .45-micron filters would be a bad idea for us, even if they were practical. One-micron filters need to be large to allow for enough flow to pass through in a reasonable time (clogged filters are bypass/overflow risks). As a result, most aquarists have settled on mechanical filtration that is between five and 50 microns. Our suggestion for most aquariums is to look for filters between five and twenty. These do a great job of letting water and bacteria through, while removing the vast majority of visible particulates.

Filter Floss (also occasionally called filter fiber) was likely the most common mechanical filtration for decades before filter socks became more standardized. The primary benefits to floss are that it is easy to replace and is relatively inexpensive, though it does not wash well, and so needs to be replaced entirely when spent. This obviously negatively affects its affordability. Some canister filters and some hang on back filters (more popular in the freshwater side) still utilize filter floss. Filter floss is frequently two colors, being white and blue, and can be bought in squares or in rolls, then cut with normal scissors to fit your individual filter. Its micron filtration is difficult to accurately measure, but you can effectively expect the equivalent of between 200 and 500 microns.

Most people with sump style filters, which is the majority of marine aquarium hobbyists these days prefer sock filters. (If you're reading this while planning a new display, go with a sump if you can.) Sock filters are more expensive initially than filter floss but are machine washable and thus reusable for dozens of washes. They are very commonly seen in 5-, 20-, 100- and 200-micron sizes. Sock filters are generally plumbed into sumps in a way that allows water to bypass the filter if the sock gets clogged, preventing you from getting water everywhere you don't want it. Filter socks have our highest recommendation for simplicity, effectiveness and cost per use. Buy a bunch of them, and then move a fresh one into the sump every couple / few days. When you have enough for a laundry load, drop them in a washing machine, with no detergent, air dry and voila, clean filter socks!

Perhaps the newest twist on mechanical filtration for aquariums comes in what is called a “roller filter” or “fleece roller.” These are also (nearly always) plumbed into sumps. Basically, when water leaves the tank, instead of flowing through floss or a sock, it flows into a box where it is forced through a sheet of filter material (of different micron sizes based on brand). As the filter sheet clogs up, the water level rises in the box, which in turn causes a series of mechanical or electronic sensors and machinery to roll out new filter sheet and the old filter sheet is taken up on a separate roll. Think of it this way, there is a toilet paper roll of clean filter paper, and once it's used, it gets rolled up onto a new filter. Once the filter that the water passes through is clean again, the water level drops to normal, and it keeps working like this until the filter starts to clog again. Like the sock/sump design, when clogged, there is usually a bypass to keep the water in the tank, not on the floor.

Rolls of new fleece cost in the $20 to $50 range and can last anywhere from a couple weeks to a couple months in aquariums with super low biological loads. They are not reusable. Roller filters aren't new technology in that a lot of industrial filtration systems have been using this method for 50 years or more, but regular adoption in home aquariums has only been in the last decade or so. This is a great bit of technology, and a really trick gadget for those of you who love new tech. They don't filter any better than a similar micron sock filter, but they do require vastly less attention. This is the only kind of mechanical filtration where you don't have to worry about replacing anything every couple day because the dirty part of the filter is removed from the water and thus the particulate matter won't dissolve back into the tank. Is the cost worth it? That's up to you.

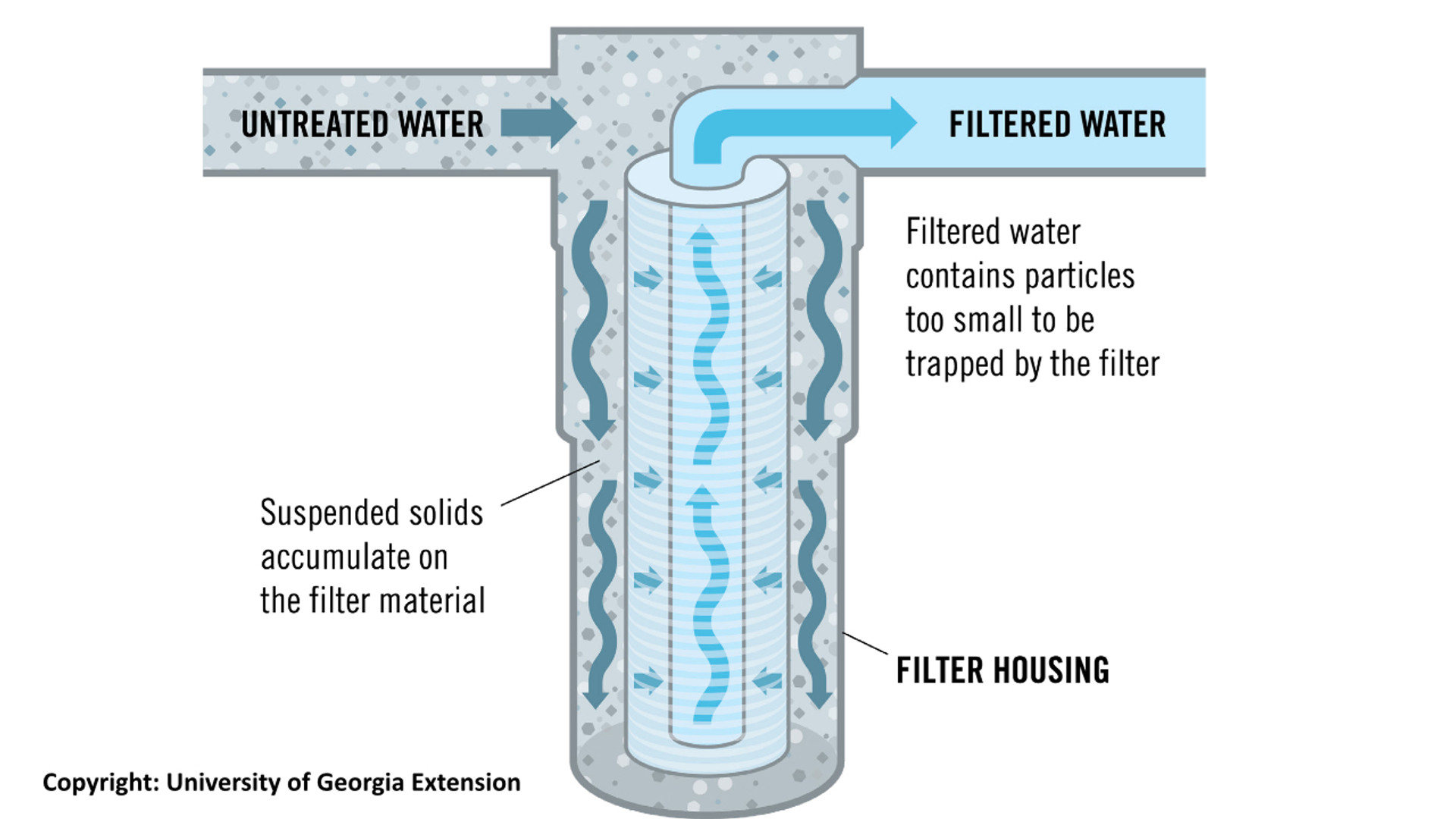

The last kind of mechanical filter that is relatively common is none. Yes, you read that right. Some aquarists run systems that eliminate the mechanical filter all together. Alternatively, they have planned a sump filter with a very large settling chamber where water moves slowly enough to allow all the large particulate matter to drop out of suspension before the water is sent back to the main display. This chamber is then vacuumed during water changes to remove any built-up sediment inside. This is obviously a budget friendly model, though biological loads can be higher in these systems, and usually more aggressive skimming must be utilized to help keep dissolved solids at bay. This methodology might be the oldest type of sediment filter utilized and is a common way to deal with solids where massive amounts of water are being purified. Versions of this exist in septic tanks and wastewater treatment plants around the world.

As you can see, there's more than one way to clean a tank, and maybe you have the next great idea about how to mechanically filter water. There isn't really a right way to get this job done, each method will have ups and downs. If you choose socks or floss, which are both time tested, just be diligent about replacing this media regularly. If you choose one of the other ways, they'll still need maintenance, just of a different sort. Next week we'll delve into biological filtration!